|

|

NOT NEWS | ||||

Details

|

The Rise and Fall of Postmodern Pop Culture

“And make no mistake, irony tyrannizes us… the reason why our pervasive cultural irony is at once so powerful and so unsatisfying is that an ironist is impossible to pin down. All U.S. irony is based on an implicit, I don’t really mean what I’m saying. So what does irony as a cultural norm mean to say? That it’s impossible to mean what you say? That maybe too bad it’s impossible but wake up and smell the coffee already? Most likely, I think, today’s irony ends up saying: How totally banal of you to ask what I really mean.” -David Foster Wallace (Klosterman, pg.208)

“That odd, the blood usually gets off on the second floor.” -Charles Montgomery Burns, The Simpsons

Introduction Native Americans used every part of the buffalo. This is an old story, and certainly not much of a story, as I’ve told it in eight words (I don’t think I’ve captured the sterile majesty of the open plains). Short old stories are useful, however, especially this one, on two levels of interpretation, as I will now explain: -short, popular, old stories make excellent memes because they’re easy to transfer so that everyone quickly knows them. -to make the transfer more exciting and relevant (thereby helping it remain in the public consciousness), the short, popular, old stories are twisted and subverted in some form so those experiencing its current incarnation can put their own personal spin on it. In this case, I am using it as analogy as how popular culture is willing to ravenously feed upon and utilize any other form of culture for its own ends. Memes like this are now transferred in ironic tones. They survive in warped states, with only tenuous connections to their source material. While an entire generation might know that it was a little old lady that asked irritably, ‘where’s the beef?’ in a Wendy’s commercial, the generation after most likely remembers it as something Homer Simpson chuckled over. It is a mocking of the meme that is appreciated differently if you are familiar with the meme in its unironic form, which is not an extraordinary request, as advertising and popular culture has preyed on such easily understandable and accessible ideas and terms in an accelerated rate for several decades now. On top of that, ‘appreciated differently’ – to get layers of a joke or reference – is not the holy grail of popular culture. The thinnest level of understanding – so you will continue to consume more of it – will do.

It’s emergence in the wake of the Second World War – when globalization was in its infancy and the transfer of goods, services, and information began to spread across the First, Second, and Third ‘worlds’ – meant that this free exchange of ideas and related products was a chief tool in the West’s face off against Communism. The transfer of cultural goods – from within Western nations or from Western nations to other regions across the globe – was a constant symbolic reminder of the advantages the capitalist system held. It certainly did not hurt that many of these regions finally began to see citizens have enough disposable income to spend on such non-essential products like television, film, and music. And when one talks of popular culture it is crucial that we keep in mind that it exists within a capitalist system, which means it is expected to have monetary worth and hopefully, for those who invest in the product, turn a profit. With any and every form of culture becoming enmeshed in this system, culture becomes an industry, and with that, “the notion that popular culture furthers a self-legitimating ideology leads Horkheimer and Adorno to claim that the culture industry becomes a filter for all forms of culture. Eventually, popular culture becomes indistinguishable from other forms of culture – all culture becomes popular culture.” (Kidd, pg.73) The time of this arrival is an important one when we consider the theoretical filter that is going to be placed upon this form of expression, as it also began to take root in the academic world in the nineteen fifties and sixties. Postmodernism is a nebulous theory that holds a rather complex array of tenets (some contradictory) with the basic ones stating that there are no absolute truths, and that many of the intellectual and social foundations that humanity bases its knowledge upon (whether it be science, religion, or simply common sense civility) are illusory. Rather than anything concrete, there is a series of interdependent metanarratives (which can be any sort of related ideas, ranging from politics to religion to the belief in progress) that hold up society like a house of cards. Coming to the fore in the nineteen fifties and sixties and becoming haute couture for periods in the following two decades, postmodernism in a way is destined to never fully fall out of fashion because it predicts (nay, demands) its own limitations and position within the larger and unending metanarrative of human understanding. What this paper will highlight is that pop culture in the early twenty first century is at a dire crossroads, with the postmodern influence of the late nineties to the present the last incarnation of what many have defined as pop culture. While longstanding mediums like the television, film, and music industries controlled most of the content and form of dissemination of popular culture, the rise of the internet over the last two decades has challenged this traditional hierarchy, with the end result being a steady erosion and narrowing of qualities – including postmodernist ones – that can be attributed to popular culture.

The New Spins on “The End” Postmodernism’s high water mark in term of popularity and influence in academia – measured in part by a spat of publications with the genre’s name in the title – was the nineteen eighties, which was unfortunate, as it would the technological and cultural advances of the next two decades which would bear out the decades-old predictions in extremely explicit and influential ways within mainstream society. Steve Connor’s Postmodernist Culture – published in 1987, with a second edition coming two years later – welcomes the MTV music video and the superficial championing of the televised image as the prime examples of how postmodernism is seen in popular culture. With a nod to Baudrillard, he states that, “a TV screen or computer monitor cannot be thought of simply as an object to be looked at, with all the old forms of psychic projection and investment; instead, the screen intersects responsively with our desire and representations, and becomes the embodied form of our psychic worlds. What happens ‘on’ the screen is neither on the screen nor in us, but in some complex, always virtual space between the two.” (Connor, pg.192) One could only imagine what Connor and Baudrillard would make of internet banner ads that are tailored to the user’s previous searches and the promulgation of reality television. Regarding film he states that, “postmodernist cinema is characterized, for the many writers who approved and extended Jameson’s analysis [that films about the past are meant to offer a nostalgic experience rather than a historically accurate one], by different forms of pastiche and stylistic multiplicity.” (Connor, pg.199) Once again, while citing such films as American Graffiti and Star Wars in the text, it is clear that nineties films such as Pulp Fiction and Fight Club would be much more effective examples of postmodernist pastiche. The purer cultural offspring of postmodernity came long after the introduction of the theory itself. Something so convoluted and indefinite takes time for it to become palpable not only for the audiences but the creators of films or music that work within a studio system or traditional facet of the entertainment industry whose goal is to reach as wide an audience as possible.

Technology played a large roll in accelerating the distribution of the archetypes of popular culture. Both radio and television packaged these familiar stories and format into even more formulaic and unchanging patterns, with act breaks always arriving at the same time in every story. Corporate sponsorship also began at this time, as certain products had their names woven into the programs titles (The Pepsi-Cola Playhouse, The Little Orphan Annie Radio Show was presented by Ovaltine, who’s ad agency wrote the episodes to boot). Beaten over the head with such stories, the public internalized them to the point where the challenge for the creators of such fare was to repackage them in slightly tweaked ways. In the wake of the Second World War, as American culture was packaged both domestically and foreign as a symbol of capitalist power, the Western – Bonanza, Gunsmoke – and nuclear family centered sitcoms – Leave it to Beaver, The Andy Griffith Show – were reinventions of adventure and morality plays, respectively. While one can certainly look back at television programming and films from the postwar period and cringe, it should be noted that much of the same culture is present today, only with more violence and sex (Crime Scene Investigation, Two and a Half Men, NCIS). The changes in format and content are minimal, while the retention of these same archetypes are dominant, and not without a degree of concern: “Baudrillard argued that modern culture and media have effectively destroyed any notion of authenticity, replacing it instead with a succession of images that purport to represent reality while, in fact, masking it from view.” (Footman, pg.251) This is exactly what postmodernism purports to be the challenge when it come to any level of objective understanding or ultimate truth. The inherent barriers of both language and human expression prevent us from attaining these realms of thought. All we have are representations of these ideas or experiences, and these limitations are also seen in the culture industry, which for the most part propagates them as opposed to a more substantial form of intellectual exchange concerning the reasons behind such propagation. The finest example of misplaced offerings of reality through traditional forms of media can be found in the deceptively named reality television. Through employing average citizens, they are typically tasked to do either wholly unnatural challenges – like running obstacle courses or eating bugs – or more common activities like cooking or assembling a business plan (albeit in front of a camera and sound crew).

‘Reality’ then, has taken on the guise of the traditional dramatic television program, with audiences following the contestants as if they were characters, sometimes – in the case of American Idol – with the opportunity to choose the outcome themselves by voting for participants. This inauthenticity exists in a medium that mingles such culture with other more important facets of knowledge, namely news programs. Granted, no one will truly mistake an anchor reporting on a natural disaster for a host of a show about competitive dancing, but the overall effect – especially when both claim to exist under the banner of ‘reality’ – is a blurring of entertainment and information. If – as McLuhan famously opined – the medium is the message, the transmission has become compromised to no small degree. While a troubling development, what in some ways can be considered a fortunate outcome is that the public seems to have properly internalized this difficulty, seeing reality through the television – and now the internet – medium as just another metanarrative. Information as a whole is now transferred in an ironic bubble, with smirking commentary the cytoplasm it floats in. So if we turn to the quote from David Foster Wallace at the beginning of this article – “I don’t really mean what I’m saying” –we find the writer concerned with the possibility that trying to understand what one truly means – that is, the truth – has become of less importance for contemporary culture and society (Wallace was writing about generation x, but it can certainly be applied to generation y/millennials as well). Right away we are confronted with the realization that this one of the hallmarks of postmodernist thought, but rather than despair, as Wallace seemingly does here, over the loss of truth, we can re-contextualize it as a subjective, personal truth. Although we may state, “I don’t really mean what I’m saying”, it does not mean to imply that we are then lying. We are at least honest about our irony, our detachment from the absolute, and that self-awareness is a good metanarrative to base a form of culture upon. These truths we now deride – whether supposedly objective philosophical statements or old stories and archetypes – retain their content but lose their overall form. It is the practice of mocking the norm/cliché up to the point that the mocking itself becomes the norm/cliché way to interact with original norm/cliché. The now-ironic content becomes its own form. It is at this moment in popular culture that postmodernism begins to take root. Throughout the sixties, seventies and eighties there were many plateaus of reinvention for popular culture, and certainly some of these steps included dipping into sub and counter cultures for refreshing and novel takes on dominant and unchanging narratives and archetypes. As postmodernism was an aesthetic philosophy as much as it could be applied to other disciplines like history, psychology, and politics, there were already examples of postmodernist culture not long after the theory was introduced in the nineteen fifties and sixties. These were not necessarily born to reflect these newer theories, but came into being as a (un)natural evolution from the modernist period that preceded it. Literature such as Calvino’s t-zero and Pynchon’s Gravity Rainbow were examples of extreme and jarring subversions of familiar literary tropes and themes. Experimental film genres like the French New Wave and Italian Neorealism did the same with the world of moving image. Yet these were typical labeled forms of ‘high culture’ that never had massive appeal at the time of their unveiling (or now, for that matter). Television, being more tightly controlled for content by media corporations and advertisers, meant there were fewer chances for postmodern tendencies to flourish at this time, but on networks run strictly on government financing – in the English speaking world, most notably the BBC and PBS – certain programming like The Prisoner and the absurdist sketch show Monty Python’s Flying Circus became cult favourites (the latter, satirizing American 50s sitcoms, one skit offered The Attila the Hun Show, with over the top bad acting, cliché violent jokes, a racist character named Uncle Tom, and a canned laugh track).

This does not mean that all prefixes with the word Pop were successful, easily understood or embraced, especially in the early going. Andy Warhol’s Pop Art meant taking popular images (Elvis, Marilyn Monroe, a Campbell’s Soup can) and presenting them in either a unique fashion (multicoloured screen prints) or as an exact replica (painting the wrapper of a soup can onto a cylinder). Subversion of pop, then, was such an easy activity for high culture, that in many circles it was meet with indifference or criticism. And while even at the time Warhol and other artists that satirized or offered homage to low culture in unique ways – Roy Lichtenstein’s comic strips, for example – were financially successful, at this point none of this was pop culture. Appealing to small niches of the modern art community and literary urban filmgoers – to rely on a stereotype – suggested that the material would never – to rely on another – play in Peoria. As Thomas Kuhn observed in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, immense, culture-altering ideas take time to grow and spread into the public consciousness. He was referring to a paradigm shift where a new scientific theory is introduced but only embraced by a small segment of academics, as only through a period – sometimes lengthy – of repeated testing and debate is it accepted by the scientific community as a whole. Similarly, offering unique forms of storytelling and turning predictable setting or character clichés on its head takes time for them to be accepted by the general public. Oddly enough, perhaps the best allegorical example of how this transfer from high to pop culture works comes from the comedy film The Devil Wears Prada, where the fashion editor of what is supposed to be Vogue dismissively lectures an intern on how an outfit worn on a Paris runaway is altered, debased, and cheapened to eventually land on a discount store’s rack. It should be noted at this point, however, that this process is not unilateral. By no means is all postmodern popular culture a cardboard derivative of postmodern high culture. Without question the influence can move both ways, with pockets of underground counter culture influencing popular culture, which in turns influences high culture (the popularity of grunge in the early nineties went from a niche music scene to a widespread youth rebellion to a fashion style on the runways of Paris). Additionally, underground counter culture can first affect high culture that in time affects popular culture as a whole. As these hierarchies are becoming less stabilized in a postmodernist period, it once again reinforces that these labels of certain types of culture – will not wholly illusory – are not absolute and are useful only as temporary markers for differentiation. Postmodernism eschews fixed positions, even if Seattle – the ground zero of grunge – always remains in the same place. Counterculture – briefly mentioned above – warrants explanation. Movements like Dadaism, the Beat Generation and Punk were ‘counter’ insomuch as they were reactionary. As pop culture became a more dominant force as the century progressed, it effortlessly began to absorb those niche societies, which in many cases existed solely to show their opposition to popular culture. Jameson acknowledges and laments this process: “Just as in the cultural sphere, the forms of abstraction which in the modern period seemed ugly, dissonant, scandalous, indecent or repulsive, have also entered the mainstream of cultural consumption (in the largest sense, from advertising to commodity styling, from visual decoration to artistic production) and no longer shock anyone; rather, our entire system of commodity production is based on these older, once anti-social modernist, forms. Nor does the conventional notion of abstraction seem very appropriate for the postmodern context” (Jameson, pg.149).

This contradiction dovetails nicely with postmodernism, a theory that can be linguistically dense and inherently paradoxical, but holding conclusions about knowledge and the transfer of information that is seen in many of pop culture’s own traits and goals: Reducing information to singular factoids, its importance and unalterable connection to a greater, more intricate and detailed system is denied. Jameson summarizes the connection thusly: “The languages of postmodernity are universal, in the sense that they are media languages.” (Jameson, pg.150) Jameson asserts then that media outlets are the harbingers and fashioners of language, having the power to alter the meaning of words for whatever agenda is being pushed. And while when it comes to politics and other disciplines with large scale social ramifications there can be quite a tangled web necessary to sort through to discover true goals, in the world pop culture the objective is refreshingly simple: profit, via reaching as many people as possible. The embracing of postmodern tenets in the nineties by pop culture was incidental. The culture industry had little interest in whether the two intellectual structures had anything in common on a superficial or deeper level. Rather, it just happened that some of the postmodernist material being created on the artistic fringes was earning an unexpectedly large amount of money (in relative terms), which made it worthwhile to pursue. It also helped that while unusual, much of postmodernism made reference – sometimes in oblique ways – to past cultural epochs and movements, which immediately gave those that absorbed the material some level of familiarity to base their expectations upon. Wheeler states that, “This form of postmodernism is not ashamed of its relationship to popular culture and the vernacular. George Lipsitz is quite right in commenting that pop music leads high art in the use of postmodern forms: ‘It is on the level of commodified mass culture that the most popular, and often the most profound, acts of cultural bricolage take place. The destruction of established canons and the juxtaposition of seemingly inappropriate forms that characterize the self-conscious postmodernism of ‘high culture’ have long been staples of commodified popular culture’ (161).” (Wheeler, pg.219) Despite originating in ‘high culture’ due to its initially unorthodox and unwieldy styles, postmodernism eventually found favour in popular culture due to it finally being understood – in an admittedly reductionist form – as a process that embraced the cross-pollination of disparate and older ideas to create something new. And as far as commodified popular culture is concerned, novelty is a trait that practically sells itself. For the larger cultural industry, the simplest way to capitalize on the sudden popularity of the novel is to alter the original intention of the work in an extremely simple fashion – with much of its original traits in tact – for the masses intended to consume it (this would be where the critics might use the term ‘clones’ or ‘rip-offs’). This is a form of industry destabilization – or detournement, to use Guy DeBord’s term for altering existing culture to give new context as well as make it more personal – is championed because it allow for a sort of blanket brand awareness, where the difference between the original and the copies are meant to be negligible. With reproductions of the authentic, we come up against yet another paradox. While initially DeBord’s detournement was meant to be done by individuals as a sort of subconscious rejection of the typical and in some ways manipulative culture that is pushed upon them (or a way to assert one’s own creative individuality), this is typically a temporary phenomena. If a certain form of destabilization is successful in its own right, creating a subculture based upon it, the culture industry typically wastes little time in absorbing the style and even the practitioners of the detournement. The explosion of punk rock is a classic example, with strains of the rejection of the dominant and popular musical styles of the 1960 and 70s largely remaining in the shadows for years, followed only by a small amount of youths on the fringes of acceptable society. Musical groups that embraced this aesthetic to varying degrees (The Velvet Underground, The Stooges) found little commercial success during their brief and tumultuous existence, but upon their innovations came future movements that would deploy their ideas and experiments into the mainstream.

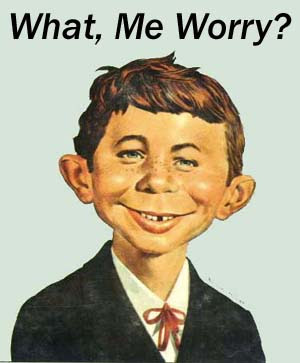

Problem soon develop, however, when one becomes keenly aware of the danger of postmodernism becoming just another one of its own conceptual victims when it becomes an entrenched theory absorbed and assimilated by society – and the culture industry – at large. Some of the unintended leaders of the movement were extremely careful when addressing these developments: “Indeed, even the most rarefied academic discussions of postmodernism, such as Jameson’s Postmodernism, have often argued the usefulness of the concept of postmodernism for anyone who would attempt to come to grips with the complexities of day-to-day life in the contemporary world… he insists that postmodernism is now a cultural dominant and that even the most mundane products of popular culture are heavily conditioned by a postmodernist paradigm.” (Booker, pg.xvii) In other words, part of Jameson’s solution is straightforwardness and clarity (obviously how successful postmodernism has been in embracing this recommendation can be hotly debated), and it just so happens that popular culture embraces such axioms. Connected to this, the clearest and most simplistic form of mass destabilization is satire. In this, one has to recognize the figure or concept being mocked, otherwise the satire doesn’t necessarily work. One of the finest pop culture examples of satire that – as coincidence would have it – became prevalent during postmodernism rise was Mad Magazine. Initially spoofing comic book stories in the mid fifties, it eventually morphed into a magazine with mock articles lampooning politics, culture, religion, people and magazines like Mad (in typical self-deprecating fashion, the writers and artists are credited on the masthead as ‘the usual gang of idiots’). Through the sixties and seventies it was a blueprint for this form of humour. Roger Ebert claimed he learned to write movie reviews thanks in part to Mad’s movie satires, a series of panels mimicking key events in the movie in question, with dialogue mocking the plot holes and absurdities of the actual film, many frequently made with full self-awareness that this was a satire of the film (with the characters referencing the film’s director, or previous roles they or other actors within the film have played). While there have been cracks in what is typically referred to as the fourth wall (that is, the awareness of the audience watching the film or play) throughout the twentieth century – notably in absurdist comedies made by the Marx Brothers or Bob Hope (the latter hoping in one of his films that his overacting might earn his an Oscar) – Mad Magazine made this an inherent feature in practically all of its mock articles. Niedzviecki acknowledges that part of what made this destabilization unique and revolutionary was the truncation of time between certain events: “So much has happened so quickly. In less than a hundred years, almost every possible rule pertaining to aesthetic culture has been broken. The notion of the specialist, the professional artist, the genius creator has been irrevocably challenged. Suddenly, we are all artists, filmmakers, musicians, thinkers. As a result, we must all take on the responsibility the artist has – of accepting nothing, relying on nothing, questioning everything.” (Niedzviecki, pg.12) Mad Magazine was ‘making’ films by satirizing already existing and popular movies, doing it in such a way that it became its own separate form of entertainment. And because it was a financial success it was no long before the film industry itself used these initially subversive blueprints to make a financially successful ‘satire’ of its own, completely in the vein of Mad. Perhaps one of the best examples is the 1980 film Airplane!, a comedy that mocks intense movie dialogue (“Surely you can’t be serious” “I am serious. And don’t call me Shirley”), 70s blockbuster films (the opening is a spoof of Jaws), popular commercials, with Marx Brothers-like vaudeville jokes to boot. This onslaught of jokes can co-exist peacefully with the paper-thin plot because it is paper-thin. By the latest 1970s, the ‘disaster film’ archetype had been embedded into the popular consciousness (Earthquake, The Towering Inferno, Airport ’75), which meant in a movie like Airplane! there could be a greater focus on the constantly destabilizing humour. The $3.5 million film made $83 million, and begat a long line of comedy films that were primarily based on turning more familiar stories on its head. With the pop culture embrace of the mocking pop culture, however, this mockery became another facet of pop culture, hostage to much of its capitalist, profit-driven initiatives. While Airplane! was a novel idea upon its release, subsequent films replicated its formula until this parody-based style became yet another archetype. With the simplicity of satire and the simplicity of making satire just another money-making, manipulative facet of the culture industry, it should come as no surprise that some postmodernist theorists decry its usefulness outright: “While realism is the dominant style of commercial media, the media do not have the deep stake in reality – effects both Lyotard and Baudrillard attribute to them. Television eats up postmodernism along with any other style available to it. Therefore parody is not intrinsically subversive, as Baudrillard would claim.” (Wheeler, pg.213) Perhaps a more accurate take on Wheeler’s explanation is that television (or film, for that matter) is not subversive for very long, as any successful postmodernist trait in this popular medium quickly becomes a standard that blunts any edge or novelty the subversive/postmodernist program originally had. Due to film and television’s massive audience, it makes sense that few pop culture endeavours push any boundaries or subvert well-worn formulas. For mediums on the periphery of popular, however, there are more opportunities for such ideas to foster and continue, appealing to a niche audience that is appreciative of such detournement. In this regard, what should also be noted concerning Mad – as well as such exception-proves-the-rule type films like Airplane! – is the age group it was targeted for, which ranged from teenagers to those well into their twenties. For those reading in their formative years in the nineteen sixties and seventies – when Mad was at its zenith, having roughly one million subscribers – the magazine was actively mocking and tearing down the archetypes that television and most of the films at that time were building up. The result of this was a generation tempered in satire and anti-establishment thinking (although not for overt political purposes). It was also likely that many political references may have at first gone over the heads of this group of readers, which introduced this group of people to the notion of the esoteric. Where one was not properly equipped at that time to understand the joke, that additional information was required. Following formulaic television programs at a young age takes little effort, but one wouldn’t get a particular political joke if they did not know who Spiro Agnew was.

Which is what we turn to now. Television was by far the most powerful distributor of concentrated pop culture in the twenty century, and at present it looks like nothing will equal it. The internet – despite its indomitable present in the Western world and rapidly growing availability in developing nations – has played a bigger role in fragmenting culture into niche rather than uniting it under a more streamlined and concentrated banner that would make it easily classifiable as ‘pop culture’. While unquestionably postmodern – due largely in the ease for individual users to personally destabilize and augment the culture offered through the medium – the internet’s diverse content and ability to subvert laws concerning copyright – which has not yet pit telecommunications corporations against media corporations – supports underground and counterculture movements to a much greater degree than ‘pop’ culture itself.

The Simpsons The quote opening this essay is from a Halloween-themed episode of the animated program The Simpsons, a weekly television series following the exploits of a dysfunctional family in the fictional American town of Springfield. This is a fine example of pop culture, as it is most likely unnecessary for me to bother with such a basic explanation of the show, as it is a global phenomenon that practically everyone – it is broadcast in over sixty nations, after all – is familiar with. But here it is, anyway. The Simpsons debuted as a series in 1990 – after three years of being shorts for the sketch comedy program, The Tracy Ullman Show and a Christmas special – as a show that was markedly different from what passed for sitcom programming at the time. It was contrasted with the most popular show in the late eighties and early nineties, The Cosby Show, which depicted a supportive, warm, upper middle class family in New York. The Simpsons, meanwhile had a mute baby, disaffected daughter, blue haired, slightly neurotic mother, and a wiseass son named Bart who was frequently being choked by the brutish, hard drinking patriarch, Homer.

With an ever expanding supporting cast – well beyond the six to eight characters that would appear on any other sitcoms with regularity – the entire town was fleshed out, as Homer’s wizened and evil boss ran for governor, the sidekick of a children’s entertainer framed his boss for armed robbery, and Principal Skinner almost joins the family as he dates Marge’s sister, Patty. But this is only the tip of the iceberg, comparable to the early twentieth century modernist take on the rigidity of Victorian/classical narrative that came before. Whereas such a program might have met resistance from audiences at other times, by the early nineties, much of comedy programming had copied either The Cosby Show’s or Cheers’ to such formulaic ends, that The Simpsons was heralded as both iconoclastic and accessible. Consequently, it was an early top twenty hit for the then-fledgling Fox Network, a status that has not wavered – although its current quality can be debated – for two decades. While the initial seasons ran on faddish popularity – Bart made the cover of Rolling Stone before the end of the first season, and had a radio hit with the novelty single, ‘Do the Bartman’ – by the third season the writers and producers were tweaking character attributes and plot pacing to such a degree that recognizable scenes of exposition and obvious joke setups were being put on the operating table and twisted into bizarre shapes. The end of the first act would sweep away all the narrative that came before and proceed with an entirely new storyline in acts two and three (‘Dog of Death’, ‘Brother Can You Spare Two Dimes?’). In some instances, dialogue delicately toed the line as to whether the entire show was self-aware of itself: Homer: Well, we didn’t get any money, but at least Mr. Burns got what he wanted. Marge, I’m confused. Is this happy ending or a sad ending? Marge: It’s an ending. And that’s enough. For a show that, despite being animated, was meant to have a more realistic portrayal of the average American/western family dynamic, it began to delve into a sense of playful absurdity, becoming less concerned with accuracy on a character-identification level, aiming for an almost paradoxical connection with its audience. One only needs to watch a handful of episodes before it becomes clear that the town of Springfield is one of the worst cities in America, despite being by critics and fans laud as a note-perfect caricature of Anytown, USA. In ‘Marge in Chains’, the town ends up rioting on two separate occasions, once over a misplaced search for a cure for the Osaka flu, which was making the rounds (Doctor Hibbert notes that, “the only cure is bed rest, as anything else I give you would be a mere placebo”, prompting the crowd to say, “Where can we get these placebos?” “Maybe there’s some in this truck!”), and the second time over their displeasure of the unveiling of a Jimmy Carter statue (one onlooker cries, “he’s history’s greatest monster!”). Homer falls off the cliff of Springfield gorge twice back-to-back, once failing to cross it on a skateboard, the second after the ambulance – come to rescue him from the initial fall – smashes into a nearby tree, forcing the back doors to open and allow the stretcher carrying Homer to roll back over the edge (in both instances we are given a lengthy and graphic shot of the fall). On a later occasion, family nemesis (although specifically Bart’s) Sideshow Bob steps onto the teeth of a seemingly endless supply of rakes for a good thirty seconds, each one rising up violently to strike him in the face. A wider shot reveals that for some reason two-dozen of them are littered on the ground in front of him. Either a punishment by the humour gods, or the fact that the episode was running short (the latter is true, which lends credence to the cliché that necessity is the mother of invention). As the show progressed, Homer Simpson became mindbogglingly stupid (misspelling ‘Smart’ as he lights his high school diploma on fire), charmingly ignorant (observing that, “it’s like David and Goliath, only this time, David won!”), and borderline psychotic (deciding to take part in army medical experiments rather than spend an evening with his sisters-in-law), and by doing so only became more endearing to viewers. While formulaic sitcom rules and television framing are easily broken in the cartoon universe The Simpsons dwells within, the connection it has to the traditional family sitcom keeps from being seen solely in this light. It is able to straddle pop culture familiarity and postmodern experimentation – while remaining a popular and profitable program – like no other television offering ever has. It’s universality and continued production (it will be starting it’s twenty third season in September) means that it has become a primary meme generator, with phrases like, “D’oh!”, “Excellent”, “Ay Carumba!”, “Haw-Haw!”, “Hiddily-ho!”, “Mmm…Donuts”, “And I for one welcome our insect overlords”, and “Thank you, come again”, entering the cultural lexicon. Even beyond ideas reducible to catchphrases, many characters grew into and also redefined the classic archetypes of whatever they portrayed. When planning the entertainment for an upcoming evening, the evil and senile Mr. Burns at first considers ‘digging up’ Al Jolson, only to be reminded by his assistant Smithers that it didn’t work out last time, prompting Burns to remark that, “the rest of that evening was something I’d rather forget” (they eventually settle on kidnapping Tom Jones). Lionel Hutz went from the show’s ambulance chasing lawyer to become the ambulance chasing lawyer. When introduced in the second season, Hutz was simply a shyster attorney attempting to sue Mr. Burns for running over Bart by having him exaggerate his injuries and bringing in a phony doctor (Dr. Nick Riviera, who would go on to become the phony doctor). His initial appearance, was still a standard stock character for a sitcom or any familiar archetype. In postmodernism, however, a character’s traits are pushed into the red, as far as it can go, typically into complete, near-unbelievable caricature. In the fourth season, there is the following dialogue between Hutz and Marge Simpson, about to go to trial for inadvertently stealing a bottle of Colonel Kwik-E-Mart’s Kentucky Bourbon: Hutz: Now don’t you worry, Marge, I- (looks down at paper in front of him) uh-oh. We’ve drawn Judge Schneider. Marge: Is that bad? Hutz: He’s kinda had it in for me ever since I kind of ran over his dog. Marge: You did? Hutz: Well, replace the word ‘kind of’ with ‘repeatedly’, and the word ‘dog’ with ‘son’.

Hutz: I move for a bad court thingy. Judge: You mean a mistrial. Hutz: Yeah. That’s why you’re the judge and I’m the…law… talking…guy. Judge: The lawyer. Hutz: Right. Now he’s barely a lawyer in name only. This extreme cognitive dissonance is played for the joke, but it doesn’t confuse the audience. We accept the portrayal of Hutz as paradoxical: while these characters became more unbelievable, they became more essential and iconic in regards to initial qualities we’ve given them. They inform a large swath of the population of how society might actually be run, and in an era when corporate influence and government inefficiency is at an all time high, the useless lawyer, corrupt mayor, and greedy boss seems less a stretch for comedic purposes than a not-too-far-off-the-mark depiction of how the world truly works. The best caricature is rooted in some kernel of truth, and when such kernels become familiar enough in pop culture, it can be shrunk to smaller and smaller until only a single term – in Lionel Hutz’s case, ‘lawyer’ – remains. This is not to say that the writers of the show had any intention of creating the cartoon equivalent of the philosophy of Deleuze and Guattari. Put simply, postmodern pop culture put much of its stock in layers of identifiable memes, only so it can subvert them. While the purpose of this is entertainment, the result is creating an audience that is passively educated in the exposure of metanarratives, and the malleability of supposed unchanging archetypes. To wit, the Simpsons quote opening this paper needs a healthy dollop of contextual explanation, while within the episode itself the viewer could piece the reference and humour without much assistance. The Halloween-themed episodes (numerically designated as Treehouse of Horror I, II, III, etc…) of the program are broken into three separate vignettes between the ad breaks. In Treehouse of Horror V, the first is a satire of the Kubrick film The Shining (itself a creative take on the radically different Stephen King novel of the same name), where the characters in the Simpsons universe take on the roles of those from the film. Mr. Burns here is reinvented as the owner of the haunted hotel, and while giving the family – led by Homer, charged with the task of being the winter caretaker – an introductory tour a terrifying reenactment from the film of a slowly opening elevator door ushering out a cascade of blood is diffused by the offhand remark printed above. Through the displacement of familiar characters within The Simpsons universe and the subversion of the original content (the film itself), a new epistemological triad is created, not unlike Hegel’s thesis-antithesis-synthesis equation. This coupling of form-content intricacy within such a popular television program has not gone unnoticed in the academic community, as The Simpsons are a popular topic for analysis. In Hugo Dobson’s article on how the show depicts Japanese culture – published in ‘The Journal of Popular Culture’ – he reminds us that, “the producers of The Simpsons are highly educated and are familiar with the object of derision, Matheson states that, ‘its humor works by putting forward positions only in order to undercut them. Furthermore, this process of undercutting runs so deeply that we cannot regard the show as merely cynical; it manages to undercut its cynicism too’ (Matheson 118). This is the hyper-ironic quality of The Simpsons’ comedy that allows us to regard the show as a more simplistic mockery or vulgar racism.” (Dobson, pg.61) Dobson here notes the episode where Homer says if he wanted to see a Japanese person he would go to the zoo, only to reveal moments later that it is because he has a Japanese friend that works there. A classy bit of comedic sleight-of-hand, twisted in a postmodern sense by having the by now lovable Homer temporarily portrayed as a racist. But while the individual jokes or obscure references can appreciated immediately or clarified with a simple Google search, Dobson insists that there a much more complex functions at work here: “The sands upon which the carnival of the family’s visit to Japan is based are constantly shifting so that for a moment Japan may be regarded as a humorous target, and the next moment American views of the world, the next moment the genre of animated cartoons, the next moment the audience’s preconceptions. Ultimately, no single position is deemed to be correct but all worthy of ridicule.” (Dobson, pg.60) Which encapsulates much of postmodernism’s most basic principles. There should be no position – political, social, or cultural – that is objectively superior to all others, or at the very least, not immune to criticism, analysis, or mockery. It is a take no prisoners approach to a system in which we are all – to some degree – prisoners. And while it at first seems that egalitarianism is at the heart of postmodernist theory, it does not take much time to see that it doesn’t get far in practice, as postmodern pop culture offers great examples of this. The obscurity of certain cultural references within The Simpsons immediately create a (admittedly harmless) boundary between people who get the joke and those that do not. Not unlike other subcultures like punk before being absorbed by the mainstream, for the moment a joke goes over a large portion of the audience’s head, stratification is created. Dobson points this out while describing a joke simple in execution, but willfully esoteric: “On board the plane, Marge tries to encourage Homer about the trip to Japan by referring to the multi-viewpoint style of Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon – a film that tells the tale of rape and murder from four characters’ testimonies of the same event that differ considerably: Marge: Come on, Homer! Japan will be fun. You liked Rashomon. Homer: That’s not how I remember it.” (Dobson, pg.61) Homer’s stubbornness at not even letting Marge be right about him liking a movie is humourous enough (there is a long line of jokes based on this seemingly-dysfunctional relationship), but buried within Homer’s retort is a direct reference to the theme of the film. The line suddenly becomes more clever than funny, appealing to people who have not only seen Rashomon, but to the few that can quickly connect Homer’s seemingly unrelated line to the alluding of the plot. It succeeds in a multitude of contexts. For those that get these references, Dobson has given offered up a rather lofty designation: “Through its use of hyper-irony and the cult of knowingness, The Simpsons hammers home Lawson and Matheson’s point that there is no arena of certainty, moral agenda, or ultimate truth.” (Dobson, pg.63) Postmodernism’s solution to this lack of certainty is to make do with the best information we have at the time and base decisions upon that. But the best information is typically having the most information. This can be seen whether its contemporary politics or popular culture. One is able to withstand the variables of modern life when they have a wider range of understanding and experience. In respect to The Simpsons, a large reservoir of knowledge is required to maximize the value of these jokes, but a very specific form of knowledge. And even that form of slowly accumulated knowledge through personal experience is dying out (in 1968, one would have to see the film 2001 to understand much of the Mad Magazine spoof of it), as the internet makes it possible to access such pools of information in record time. So much so that retaining the information – whether for personal pleasure or the intention of transferring it to another inquiring mind when the opportunity arises – is not nearly as important as having the ability to call it up at a moments notice. A knowledge of particular messageboards, Wikipedia articles, and the best word combinations for a Google search has superseded the knowledge these databases contain in importance. What is remarkable is how tenuous this form of knowledge is. It require a constant and unbroken connection to the internet – a sort of shared memory we all can participate in – which itself relies on a vast network of energy resources, satellites, servers, and monitoring by hundreds of corporations and agencies. While large steps have been taken to ensure that a wireless network in one’s neighbourhood is as reliable as electricity and clean water, other threats outside of infrastructure – hacking, computer viruses, a lack of standardization in certain respects – is a reminder of how our contemporary information sources are impermanent and not absolute. This awareness is one of the most the difficult to properly embrace, as it acknowledges the fragility of the foundation human understanding is built upon. And good postmodern pop culture has no qualms with turning this awareness upon itself, as The Simpsons have frequently shown. At one point Bart complaining about all the old cartoon character balloons during the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade. Homer reminds him they can’t make a balloon out of every ‘flash-in-the-pan cartoon character’ without ruining the parade, just as a Bart Simpson balloon floats by: “Thus Bart watches himself as popular phenomenon on television. The Simpsons television program thereby acknowledges its own characters’ status as popular icons whose circulation and reception are worked back into the ‘text’ itself.” (Collins, pg.197)

Fredric Jameson takes a more positive spin on this destabilizing: “What happens here is that each former fragment of a narrative, that was once incomprehensible without the narrative context as a whole, has now become capable of emitting a complete narrative message in its own right. It has become autonomous, but not in the formal sense I attributed to modernist process, and rather in its newly acquired capacity to soak up content and to project it in a kind of instant reflex. Whence the vanishing away of affect in the postmodern: the situation of contingency or meaninglessness, of alienation, has been superseded by this cultural renarrativization of the broken pieces of the image world.” (Jameson, pg.160) The Simpsons’ parody of The Shining – pronounced ‘The Shinning’ – becomes a pop culture event of its own, absorbed in a myriad of ways depending on how familiar the viewer is with the original, but this connection isn’t meant to suggest a hierarchy of value based on that familiarity (Dobson’s ‘cult of knowingness’ stresses difference, not better or worse). Regardless of this awareness, each viewer participates in genuine renarrativization. Once again, contemporary technology plays a great role in defining this relationship between culture and consumer. The speed and fragmentation of how culture is absorbed is reflected in both the style and format of the popular culture itself. Comparatively, in Bradbury’s 1951 novel Fahrenheit 451, the protagonist – a government employee who is ordered to burn books – finds himself confronted with an underground reactionary group who together has memorized several books and other forms of literature they believed are culturally significant. Paradoxically, while television coupled with the internet can be said in many ways to eradicate this form of remembrance, once the references themselves are connected to the dialogue from the cultural epoch (in this case, a Simpsons episode), it is this meme that lives on in the individual’s memory banks. Even an occasional viewer of the show could recite a favourite line or two, while certain aficionados could certainly rattle off all the best lines from an particular episode (in the interest of full disclosure, many of the quotes in this paper came right out of the author’s memory, with only quick internet searches to double-check the phrasing). The Simpsons are a particularly useful example for postmodern pop culture, as compared to most television programs or other examples of popular entertainment in general, it spans the globe in numbers that no others match. McDonaldization has been the derogatory blanket term for American cultural dominance, and while going to a Golden Arches restaurant anywhere in the world can perhaps be considered a postmodernist phenomenon – an immediate and disposable meal void of any local cultural value or history – an intelligent, thought-provoking, self-critical television program makes for a far better ambassador of the same culture. Among one of The Simpsons inherent advantages as a tool for pop culture detournement is its ‘inhumanness’, that is, the fact that it is a bunch of drawings representing people makes it easier for all viewers to recognize sitcom-like allusions while being more prepared for a challenge to these archetypes. Animation is a particularly successful art form for the infusion of postmodernist ideals as there is already a level of unreality to it. Whether the program follows a four-fingered yellow family, one from the Stone Age, or anthropomorphic fast food (Aqua Teen Hunger Force features a container of French fries, a milkshake, and a meatball among its lead characters), the viewer is now better acclimatized to contextualizing a tire fire burning since 1989, cynical talking dinosaurs, and lead characters being created for the sole purpose of being shot into a wall. This is not restricted to entertainment primarily aimed at young adults and above (with The Simpsons being classified as a program meant to appeal to teens and adults). Entertainment for children has long used such destabilizing practices to amuse. What began with Looney Tunes in the 1940s – animator/director Chuck Jones acknowledged they tried to find what the makers of the cartoons found funny, not necessarily tailoring the animated shorts to any one age group –continued with such programs as Rocky & Bullwinkle, Tiny Toons, Animaniacs, and at present provides us with Spongebob Squarepants and Adventure Time with Finn and Jake. A great majority of children’s programming is akin to typical pop culture fare, in that it follows traditional storytelling themes (the distinction between good and evil, the pacing of the narrative, the clear and uplifting resolution), so it becomes the responsibility of a few key television series like those listed above to tear down these archetypes just as they are being built up in contemporary youth (frequently with amusing results). Through this process, within the historical context of the late twentieth century, generation x and (to a greater extent) generation y have grown up with the notion that almost all pop culture is carefully manufactured and superficial, and is most comfortable with it when it is mocking its own ability or self importance. Or, as two disaffected teenagers say on The Simpsons: Teen #1: Oh, here’s that cannonball guy. He’s cool. Teen #2: Dude, are you being sarcastic? Teen #1: I don’t even know anymore. Almost fifty years earlier, the equivalent was almost indistinguishable, with Daffy Duck turning to audience in the middle of a rant and asking, “What’s Humphrey Bogart got that I ain’t got?” The irascible mallard is also the protagonist in what is probably the most famous and accessible postmodernist cartoon, Duck Amuck. Chuck Jones said of the cartoon that it was engaging with the audience to question just what is a ‘character’? What are their defining traits, and how recognizable are they without them? Throughout it’s six and half minutes run time, an off-screen animator – with godlike powers thanks to a constantly interfering pencil or paintbrush – tortures poor Daffy by erasing parts of his body and replacing them pieces from other animals, turns him mute, duplicates him, and takes him from a snow to beach to blank screen settings in mere seconds. Throughout all this, the ‘idea’ of Daffy persists.

Carl (noticing the new and unusual décor in Moe’s bar): I don't get all this eyeball stuff. Uh, what are they supposed to represent? Uh, eyeballs? Moe: It’s po-mo. [blank stares from Carl, Lenny, and Homer] Moe: Post-modern. [continued blank stares] Moe (somewhat dejected): Yeah, all right, weird for the sake of weird. [all three nod in understanding]

The Swan Song of The Great Leveler The Simpsons’ ‘human’ counterpart was the other surprisingly popular (considering its humble beginnings) show of the nineties – the show about nothing – Seinfeld (which debuted only sixth months earlier). “No hugging, no learning” was the show’s unofficial mantra, with the four central characters typically void of emotional connections found in other popular sitcoms at the time. Interacting with a bevy of other characters with disastrous results (people get fired, arrested, deported, bankrupted, and even killed due to their meddling), there is typically no punishment doled out upon them (breaking perhaps one of the most basic morals of storytelling). They are unscrupulous enough to even plot against each other at times, but still remain a cohesive, perplexing, and fascinating cast for all nine seasons. While The Simpsons pushed traditional sitcom archetypes to the absurdist extremes, Seinfeld went the other way, examining in fine detail the minutiae of everyday life (episodes revolved around waiting for a table in a Chinese restaurant, getting lost in parking garage, or lying in job interviews).

When the show did adhere to the more traditional pacing of a situation comedy (an episode with a single plotline), they dragged it out at a glacier-like pace. ‘The Chinese Restaurant’ episode took place in one location for the full thirty (twenty three) minutes: a waiting room of a restaurant, as Jerry, George, and Elaine wait for their reservation to be called. Without question the most postmodernist aspect of Seinfeld was its story-arc concerning the character Jerry Seinfeld being approached by NBC executives to create a show about his life, essentially recreating the real-life genesis of Seinfeld itself. Jerry Seinfeld and Larry David created Seinfeld, and in the show Jerry Seinfeld and George Costanza (an acknowledged Larry David-surrogate character) created ‘Jerry’, with the latter being a carbon copy of Seinfeld itself, right down to the personalities of the four leads. This level of self-reflexivity was executed to perfection, rewarding both hardcore and casual fans of the series with a wholly unique but believable narrative concerning the daily life of comedian Jerry Seinfeld, real or televised. Viewers were reminded constantly that what they were watching was a television program because these series of episodes concerned the creation of such a program within the show’s universe. Seinfeld ended in the spring of 1998 as the most popular show on television. Nothing would replace it – whether in terms of comedy or drama – in terms of combining groundbreaking style and form and commercial success. This was due to a series of technological advances that changed the medium forever. The early years of the internet acted as a promoter and almanac of television programming, as bandwidth was not yet powerful enough to support downloading or streaming of audiovisual files. Early personal webpages or newsgroups would devote pages of text concerning television, film, and music that were still mainly experienced through other mediums. The internet provided a virtual location to post opinions on the popular culture witnessed by millions at more or less the same time, thereby strengthening the connection between aficionados, physical distance no longer a barrier for socialization. Focusing on popular culture that was released with postmodern facets in the late 1990s and early 2000s means that it dovetailed with the high-water mark of television as a traditional, communal experience. While postmodern fare was finally reaching larger audiences during this period, changes in technology that were distinctly postmodern – giving the audience more freedom, old absolutes falling by the wayside – were on the horizon. A combination of speed and accessibility had improved to the point where downloading larger and larger files – or streaming live video – over the internet was becoming possible. While initially this sharing of documents was mainly reserved for music files – as audio files were still smaller than audiovisual files – it was not long into the new millennium that the size of the normally resilient television audience began to plummet, as other forms of entertainment was luring people away (sometimes to watch the exact same program, only this time at their own convenience without ads, and not when regularly scheduled). The other advances were the two devices that allowed for the TV watcher to better tune their TV watching to their own whims. DVDs (Digital Video Discs) meant concentrating the information on several videotapes onto a single disc, which meant that a television series’ entire season could be placed in a relatively small package and consumed at the viewer’s leisure. The need to be in front of one’s television, same bat time, same bat channel, had dissipated. If one was patient, they could avoid the television program – and the ads that paid for it – during the television season and instead buy the DVD set and watch all the episodes in a marathon viewing session if they so chose (a popular choice for more episodic fare like 24 and Lost, the latter having some of the most unusual narrative subversions of the last decade). On top of this, the Digital Video Recorder (DVR) was able to do away with the DVD entirely. Essentially a hard drive plugged into a television offered by one’s cable provider, the device allowed one to record television shows simply by specifying the starting or ending times – or highlighting the program from a menu – where it will remain stored until one wishes to view it. What was considered ‘popular’ in pop culture was becoming harder and harder to find. While the study of ratings was never an exact science – with methods ranging from people simply writing what they watched at certain times in a logbook to a small device that tracked what channel you were currently on – viewership has unquestionably declined. While the immediate consequence is a loss of a uniform and collective experience across various communities, the loss of advertisers (or lower of advertising rates) is one of the most devastating blows to postmodern pop culture, as it meant that each television series had a shorter period of time to make an impact in the ratings and connect with audiences (with Seinfeld being the classic example of an unusual program requiring a few seasons of middling ratings before becoming popular). Few networks are willing to lose money over several months to allow a challenging program to find a steady demographic of patrons. Middle-of-the-road dramas, unoriginal sitcoms and inexpensive reality shows have become the norm on network television, which for decades has been (along with the media coverage of its programming) the de facto source for an instantaneous litmus test for pop culture. Cable television – where subscription fees replace advertising dollars – is a better place for more unusual and complex series to flourish, but it still must face (illegal) internet downloading. Additionally, its smaller audience means it might not be able to considered ‘popular’ at all (the exception could be considered HBO’s The Sopranos, but even that was soon placed on more basic cable network schedules to help diffusion). Programs like Mr. Show and The Larry Sanders Show pushed boundaries in terms of form and content, the former and absurdist sketch program in Monty Python vein (helping launch the careers of David Cross, Jack Black and Sarah Silverman), the latter helping introduce a no frills, documentary style of filming way of capturing a more traditional sitcom-type set up (behind the scenes of a late night talk show). Postmodernism is known for its pastiche-like quality, that is, bringing various styles and ideas together to create a new work. As the two 1990s programs listed above – from the slightly higher cultured premium cable channels – poached from british humour and cinema verite respectively, so to do the more egalitarian traditional networks borrow from them. The documentary format has yielded both The Office and Modern Family, which eschews the much-maligned laugh track – a staple of pre-postmodernist comedy programming – and has characters addressing the camera directly from time to time, mean that there is an awareness that this is a program of sorts, meant for entertainment or (in the character’s world) education. In some respects this is taken even further by adding a narrator, the most successful (in terms of critical and cult attention, certainly not ratings) being Arrested Development, airing for three seasons – each one shorter than the previous – before being cancelled. Following a dysfunctional family’s slide from riches-to-rags, creator Mitch Hurwitz and the writers created what might be considered a live-action Springfield, an expansive universe within the show full of quick, barely noticeable gags foreshadowing future events and catchphrases that – rather than becoming property of a single character – is passed around like the church collection plate. On several bizarre levels, Arrested Development harkens back to the 70s sitcom Happy Days, which romanticized the 1950s. The narrator of the show – Ron Howard – played protagonist Richie Cunningham on Happy Days. The family lawyer on Arrested Development is played by Henry Winkler, who played ‘the Fonz’ on the former. Scott Baio’s character Chachi later replaced ‘the Fonz’ on Happy Days when the producers though he was getting too old, and Scott Baio played a lawyer who replaced Winkler’s character on Arrested Development. To top it off, the Fonz’s waterskiing over a shark on Happy Days was seen as the moment when the show became more ridiculous than relevant, spawning the catchphrase decades later, ‘jumping the shark’, to describe any show that is no longer embraced the way it was. On Arrested Development, Winkler’s character hops over a recently caught shark on a dock. Much like The Simpsons sign gags that are only onscreen for a second (outside the Cathedral of the Downtown: “Archbishop carries less than $20”), these minute bits of humour create a new form of viewer. One who lives for this fragmented exclusivity, who can imagine that there is a private club or form of understanding for those who are willing to work just a bit harder to see where these other like-minded people creating these pieces of culture are coming from. And essential to postmodernism’s openness, anyone can join these groups if they pursue these information channels. Ideally, the greater the knowledge on behalf of the viewer, will offer up a unique, nuanced viewing experience for them. At the same time, these optional practices of the viewer are in some ways anathema to the inherent disposability to pop culture itself. Despite the fact that postmodernist pop culture will poach from previous incarnations of pop culture does not guarantee its immediate and runaway success, currently demanded by the television industry. While these programs may exist on a medium that still attempts to appeal to both broad and narrow viewer demographics (30 Rock – a sillier take on The Larry Sanders Show conceit – is an example a program with plenty of postmodernist hallmarks that doesn’t do well in the ratings, but attracts a key youthful demographic), the challenges that television faces in the second decade of the twentieth century has, overall, meant appealing to the least discriminating audience comes first, and at the expense of more challenging and unique programming. In the cases of The Simpsons and Seinfeld, time was granted for their postmodernist leanings to be accepted by a wider audience. The former, a ratings hit immediately, slowly ushered them in over several season, while the latter introduced such ideas right away, and took several years to let the audience become familiar with the playing of the form. These two programs made such an indelible mark on the shaping of contemporary pop culture, however that even watered down versions of their ideas and subversiveness can still be found. The mere fact that reality TV mimics the sitcom/drama formula over the course of its hour or half hour – while mocking the formula within the show itself – shows how self-awareness has become an archetype unto itself. There are many advantages to this process, regardless of the form of culture in question. To know the rules (to create a believable universe, when there is an exterior shot of a public building there is a typically a sign out front, just like in real life) and then subvert them (have the sign in question say something completely silly or absurd, like ‘God welcomes his victims’ outside a church after a hurricane in Springfield), means you have control over them. By allowing the viewers to make these connections themselves – not leading them to water, but hinting where the well might be – you are giving them agency in an activity that for a long time has been a relatively passive one. DeCerteau maintains that this constant tweaking of rules and archetypes in the world of culture is in part an opportunity for those lacking true power (political or financial) to participate in some small way to making their voice or position heard. Not necessarily for political or social gain, but simply to have some level of acknowledgement that they do indeed have a singular identity with unique interpretative powers. Despite the incredible amount of technological and social advances through the 1900s Niedzviecki finds that little regarding the perception of mass culture and its connection to the commercial-industrial economic complex has changed by the end of the twentieth century, in fact, the desire for it has been amplified. Discussing a local underground music group named Braino, he notes that, “the band is, effectively, doing what we are all doing in our lives: reordering mass culture, interpreting it to have a meaning that allows us to stand defiant in the face of generic anonymity we are otherwise doomed to.” (Niedzviecki, pg.14) In an increasingly fragmented society where bureaucracy is perhaps the most oppressive and unwieldy opponent for the individual and their own pursuits, taking solace in a small niche of culture is a small but personally significant gesture. Television with obscures references was a first step in the realm of popular culture – and the few shows that masterfully balanced these qualities with widespread appeal were key postmodern pop culture specimens – and while the diffusion of the amount of programming was a first nail in the coffin for the mediums concentrated power, it was the internet that not only replaced the idiot box, but destroyed much of its precepts as well. This fragmenting of culture – popular and non, postmodern and non – results in less community and more autonomy, for better and for worse: “We lifestyle culture adherents reject those who long for the days when there was a central moral authority that could authorize art and rein in our slavish devotion to entertainment culture; we reject the cultural capitalists who see us as nothing more than numbers, consumers tricked into buying what we supposedly don’t need, and adopting viewpoints that often run counter to our interests and our experiences. Through lifestyle culture, we reject all of them by attempting to reshape the cultural forces swirling around us.” (Niedzviecki, pg.27-28) In many respects this has become the norm, where programming or culture that does not offer this layer of detail is derided as cheap and superficial; the ‘true’ pieces of pop culture that many critics like to deride as poor quality fare for the lowest common denominator. For a little over a decade television’s biggest shows were distinctly postmodern, but postmodern technological advances complicated how the medium that for many years exemplified popular culture reaches the masses.

The Two Minute Movie Brevity is a welcome format for postmodern pop culture. Only the basic archetypal story structures are required for them to be adequately subverted, and a twenty-two minute, three-act television program is well-suited for such a presentation. With film – especially those of feature length, which is typically a minimum of eighty minutes – many more challenges arises, typically with the handling of the narrative. Postmodernism is immediately suspicious of narratives. The narrative of history is a classic example of how interpretive and multifaceted complex structures can be, and the danger that exists of making contemporary decisions based on limited knowledge or particular goals in mind While film might not be as pressing as history, it is a form that supports the notion of a clear and concise progression of events and thereby reinforces the belief in contemporary culture that certain events and situations can be linked casually with limited discussion or insubstantial research being applied to them. Consequently, postmodern film would be of the sort that questions these narratives and certain contemporary values. While many films have successfully challenged the more traditional narratives and styles these narratives took, more often than not they were meet with derision or criticism upon their release, with commercial success often elusive, thereby not falling under the banner of postmodern pop culture. Much of the work of Stanley Kubrick comes immediately to mind, as do the films of David Lynch. Both of these writer-directors are regarded as auteurs, with their idiosyncratic styles of filmmaking challenging how the audience engages with film structure itself. In the initial years of postmodernism, Kubrick offered up Dr. Strangelove, a black comedy concerning the threat of nuclear annihilation with actor Peter Sellers playing three lead roles, following it up 2001: A Space Odyssey, a two-and-half hour science fiction film with only twenty three minutes of dialogue, remarkable special effects, and only the insinuation of extraterrestrials. Initial reviews were initially mixed for both films (the former being accused of mocking an extremely serious subjective, the latter for being pretentious and incomprehensible), although each found some level of commercial success, with 2001 becoming especially popular with the counterculture demographics of the late nineteen-sixties. While the mid sixties to late seventies was seen as a great time for the merging of experimental and mainstream films in the West, thanks to profitable blockbusters like Jaws and Stars Wars – although it should be mentioned that both films are masterpieces of the adventure genre – the movie studios quickly re-appropriated control of how movies could be properly marketed to the public, which include involving themselves in the filmmaking process. The fight between filmmaker and movie studio could best be seen over the final cut of Terry Gilliam’s sci-fi noir film, Brazil, with the director butting heads for many months over his vision of a dystopian industrial future and the studio wishing for an upbeat ending and pop-infused soundtrack. Risk taking independent cinema only became of interest to the major film companies when it seemed possible that it might turn a healthy profit. While a handful critically lauded films seeped into theatres – soon to be almost wholly replaced by multiplexes – in the eighties and early nineties, it was not until Quentin Tarantino’s 1994 Palm D’or winner Pulp Fiction grossed 200 million dollars worldwide – on a budget of $8 million from the then still blossoming independent movie company Miramax, run by the Weinstein Brothers – that the opened the floodgates for postmodern influence to be injected into Hollywood. Pulp Fiction was seen as one of the first financially successful pastiche films of the postmodern pop culture era. Many of its themes, narratives and characters are familiar to B-movie aficionados, but clever roundabout dialogue and a non-chronological storyline gave it both character depth and a destabilizing allure (we watch certain characters die midway through, only to return later on). Booker states that Pulp Fiction, “did more than any single film to popularize the hyperlink narrative form in film” (Booker, pg.13). That is, its connection to other film genres and styles are both on the surface (having John Travolta – star of the disco film Saturday Night Fever – dance now as a sleazy hit man) and embedded within its framework (referencing 70s British gangster films, French New Wave, and Japanese samurai films).